Listening at Scale

Effective listening is arguably the most critical skill for HR professionals. To address workforce needs, HR team members must be proficient in active and attentive listening. Gathering information about the workforce is as vital to an HR team as air and water.

To listen to a member of the workforce is to give them respect, time, and attention, and to hear what is going on. It’s the oldest way we learn. We’ve seen listening programs grow from those roots into programs that survey the full company and beyond.

I’ve often referred to people analytics as "decision support for HR," but another phrase I’ve used is that people analytics can be described as "listening at scale." To date, that’s been treated as more a metaphor for how we work with data rather than adopting systems data and people analytics into the listening ecosystem.

However, I believe we can take this further and fully integrate the analysis of workforce systems data into an integrated framework for information gathering and listening.

Understanding People: A Three-Channel Framework

Margaret Mead, an anthropologist, best captured the complexity of working with humans with her quote: “What people say, what people do, and what people say they do are entirely different things."

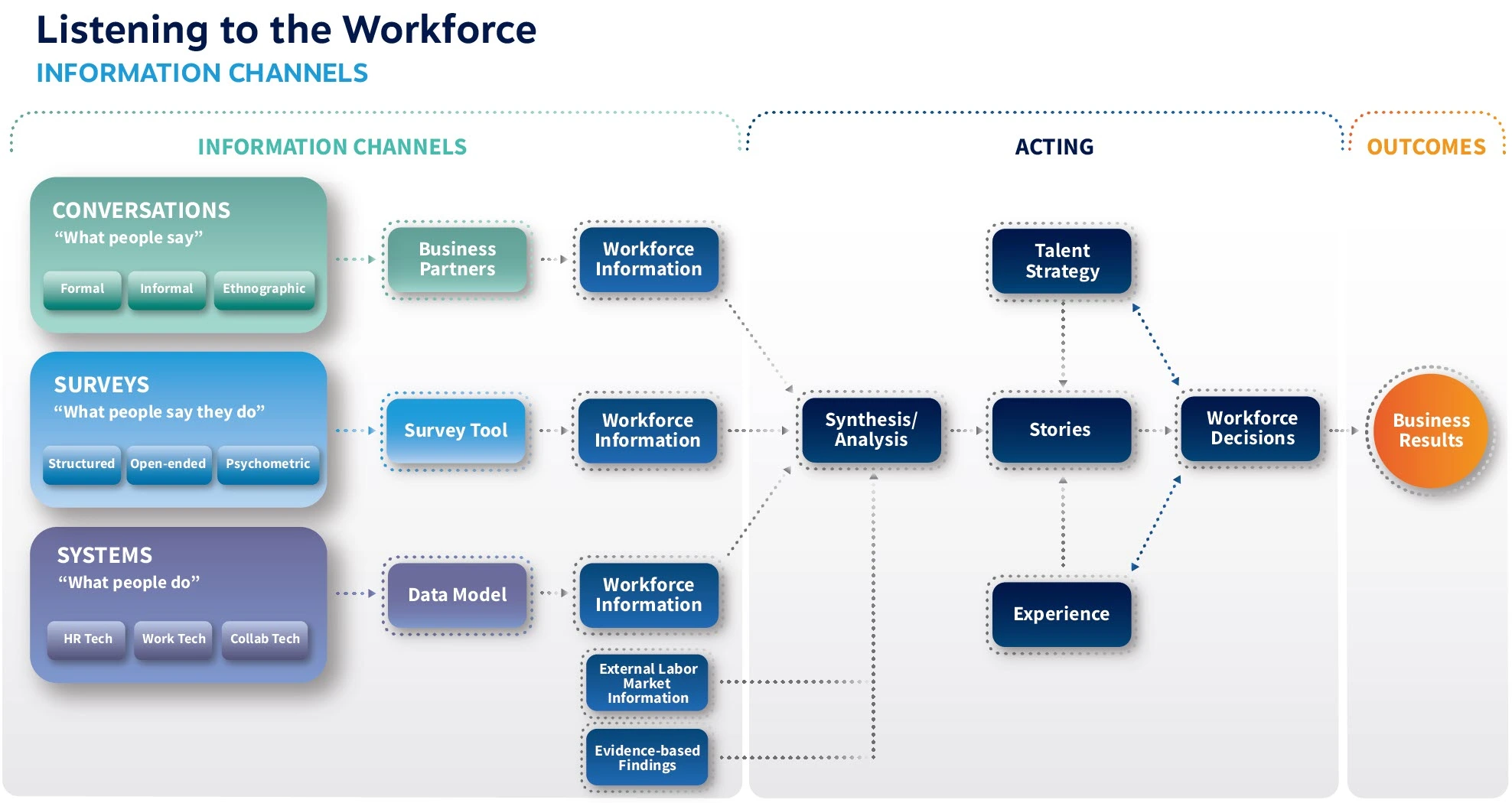

While humorous, I believe this quote can also act as the foundation to inspire an integrated framework for workforce listening. Mead's quote effectively outlines three “information channels” for gathering information about the workforce: conversations, surveys, and systems. I’ve rearranged them slightly for the purposes of this blog:

- “What people say” = Conversations: People having conversations in the workplace

- “What people say they do” = Surveys: Respondents assessing themselves and their ideas through surveys

- “What people do” = Systems: What people actually do in the workplace which can be tracked within HRIS or collaboration technologies (HR Tech / Work Tech / Collaboration tools)

And I am very careful to say information channels above. As I’ll detail in this article, conversations, surveys, and systems are where workforce information is generated. Data and insights then flow from those channels to central storytellers and decision-makers. This is an end-to-end view of the HR decision-making process.

This is an alternative way to view data to how we usually discuss data in HR. We often hear data described by its topic (e.g. Recruiting data, L&D data, or Comp data), source system (e.g. Workday data, Greenhouse data) or its application (e.g. descriptive, predictive, prescriptive data). This channel view seeks to depict the supply chain of information.

Let’s delve deeper into this framework to create a more comprehensive understanding of the workforce. I believe this holistic approach to listening will allow HR professionals to make better-informed workforce decisions that positively impact the organization.

Conversations

Speaking to the workforce and making use of that information to support decision-making is how we got our start as an HR profession. Conversations refer to the 1:1 interactions, observations, and ethnographic tools that HR employs to understand the workforce. These are very human tools and these tools can be a powerful method for sense-making and storytelling within an organization.

When conducted effectively, conversations allow HR personnel, managers, and leaders to gain a nuanced understanding of their workforce that technology struggles to replicate. For instance, it will be a long time before computers can comprehend how grief impacts performance, the unsettling chaos of a reorganization, or the pride of a promotion. Despite recent advances, empathy, connection, and meaning-making will remain distinctly human domains for some time.

In the move towards data-driven decision-making, I believe we have underestimated the impact that these conversations can have on decision-making. The anthropological sensemaking that occurs when an experienced HRBP listens to the workforce is unmatched when it comes to quickly understanding cultural dynamics and understanding the core of workforce issues.

Bias and human error in this channel of conversations is a well-documented concern and there are dangers in relying solely on conversations to inform the HR decision-making process. These are issues that must be thoughtfully planned for and mitigated, both in how this method is employed, but also the use of other channels to validate, verify, and correct for bias in information gathered from this channel. However, that does not mean that those other channels will replace conversations and conversation still has an important place in decision-making.

I see three breakouts within the information channel of conversation:

- Formal Conversations: These include regular 1:1s, performance reviews, and formal checkpoints that ensure the workforce is heard, managed, and supported. These conversations not only help managers and HR leaders evaluate their employees' performance but also provide an opportunity for information gathering for the organization and for understanding the employee experience.

- Informal Conversations: This refers to the casual conversations that take place around the “watercooler” (in person or remote), where employees can share what's really going on. These conversations can lead to surprising insights about the workplace, culture, and organization. For instance, employees might discuss work-related challenges, share ideas for improvement, or provide feedback on a topic that you wouldn’t expect. Such conversations can help managers and HR leaders identify potential issues before they become problems, and can be a channel for business context that is not otherwise captured.

- Ethnographic research: The most formalized version of conversation-based information gathering would be ethnographic research. This refers to the scientific and qualitative research techniques such as observation, participation, and immersion in the workplace to gain cultural and organizational understanding. Ethnographic research can provide a validated and scientifically sound understanding of employee behavior and attitudes, and can also uncover hidden dynamics and cultural norms that might not be apparent through formal or informal conversations alone. By conducting ethnographic research, organizations can gain a deeper understanding of their workforce and tailor their strategies and policies accordingly.

Want to see how One Model turns conversation

data into analytics?

Survey

This channel refers to the toolkit around the scaled collection of novel data. I use the word Survey as surveys are a great example, but this channel represents whenever a form is completed to capture novel data that is otherwise not captured by a system passively. This includes engagement surveys and other forms such as filling out performance reviews or feedback forms after trainings.

Surveys are a method to gather information from a large amount of people quickly. I could spend 30 minutes speaking to 80 people (a full back-to-back week for me and a 30-minute disruption for every person I speak to) or I could design and send a survey that everyone completes on their own time. Surveys can provide a structured, valid, and reliable method to collect information about workforce attitudes, opinions, behaviors, and demographics.

Some breakouts for the survey:

- Structured survey questions: Questions about the environment, factors in the workplace, and information that the creator wishes to assess. Ideally structured and evidence-based. Questions could include items like "How satisfied are you with your current role?" and "Do you feel valued by your employer?" followed by a distinct multiple-choice scale.

- Open-ended survey questions: Open-ended survey questions provide a prompt with a text box for a respondent to complete. These questions could include a variety of open-ended topics like “please tell us about your onboarding” or “Are there tools you need to perform your role that you cannot acquire?”. The volume and variety of data that is brought back through open-ended surveys is much higher than structured surveys and these require further coding or understanding before they can be used in decision-making.

- Psychometric surveys: Psychometric survey questions could be either structured or open-ended, so this is a bit of a false breakout, but it is important to call out as it is a unique type of information gathered about the psychology of the employee in the workplace. Psychometric surveys gather information about employees' attitudes and sentiments which can be helpful in understanding variations in trends such as attrition.

Systems

The third internal information channel in this framework is systems. As technology is increasingly integrated into workplace operations, the workforce’s interactions with technology generate a wealth of data about people, processes, and work habits. Skilled data engineers, analysts, and data scientists can process this data to extract valuable insights about the workforce.

The key advantage of systems data is its readiness for use, as well as the growing volume and speed of its generation. Systems data exists already for nearly every aspect of the work experience today, from hire to termination and from performance management to learning. This broad dataset, when properly extracted and prepared, enables more sophisticated data techniques to be brought to bear faster compared to the other channels.

Systems data can also offer a broader perspective of the organization as a whole. Conversation and surveys gather information from each employee from their personal viewpoint, but their perspective may not be broad enough to see organization-wide issues. The view of what is going on end-to-end, which is needed for workforce planning, workforce readiness, or skills gaps analysis, can be generated from this systems channel.

Systems data is also valuable because it is largely a passive data source, produced as a byproduct of work conducted through technology. Consequently, it is less subject to biases and limitations of human perception, memory, or interpretation.

However, systems data often lack the nuanced information density of business context provided by conversation and survey methods. Additionally, the bias it does have is often embedded in the software design choices which can often be harder to detect and understand. Choices made by programmers regarding UX, data capture, native reports, and interactions available can introduce potential areas for bias in the extracted information.

Systems data can be further categorized into three main breakouts:

- HR tech: This is the traditional tech stack managed by HR tech teams. Systems handling HR-related processes and programs (e.g., Core HRIS, ATS, Performance Management, LMS). For example, when a worker is hired, the applicant tracking system (ATS) captures data about their demographics, prior experiences, and the interviewing team's assessment.

- Collaboration Tech: Systems capturing collaboration (e.g., Slack, Microsoft Teams). These tools (Slack, Teams, Zoom, Google Docs, etc.) produce information about teams, interactions, and how work gets done within an organization. Techniques like organizational network analysis can reveal how information flows through an organization or identify influential individuals.

- Work Tech: Technology capturing broad work data outside of HR tech (e.g., procurement systems, code tracking, or attendance). Systems like intranets, timekeeping, expense systems, and ticketing systems. These work tech systems also produce data that can be used to recreate, model, and analyze the flow or work in the workplace. By associating these systems with HR tech systems, we can build powerful stories connecting HR data to work outcomes.

Tradeoffs in Information Channels

Selecting the right channels for a given decision is vital for success. To do so I see the need to weigh the tradeoffs in trust, effort, and information density.

Trust

Trust is a key factor in how we interpret information that comes from the various channels. For instance, information from conversations can be difficult to trust, particularly when not everyone involved is present or when they are not recorded, transcribed, or made public. If I talk to my manager about a coworker, my manager will need to verify their side of the story. Even when conversations are recorded, they can still be misleading.

Surveys are generally more trusted than conversations due to the structured way that they are delivered. Surveys can have academic ties on their design and are typically more consistent, reliable, and objective than conversations. That said, it can still be difficult to know what someone was thinking when they read a question on their own. Employees may also have an incentive to game a survey or mislead the survey, which can lead to reduced trust.

Lastly, systems data is considered to be the most trusted type of data because it is generated as a byproduct and (optimally) unchanged from when it was generated. Unlike conversations or surveys, systems data doesn't rely as much on interpretation as there is not as much subjective context. Instead, the systems channel provides information simply on the actions that have occurred. As a result, systems data is often seen as a more trusted source of information.

Effort

The effort required to create information from each channel is another consideration. Conversation data is rarely converted into what we think of as data that we could interact with in a spreadsheet (tabular) but is usually synthesized and interpreted by each person who had the conversations. Making sense of many conversations and even having to have many conversations makes this channel high effort to scale.

Survey responses are much easier to information due to consistency and the planning involved in creating a survey tool. The data that comes back from closed-ended surveys and many psychometric surveys can be quickly analyzed in tabular formats. For open-ended surveys many of the concerns of conversation come back in, but on a more contained scale.

As stated above, the systems channel produces data that is relatively ready to use. While getting data extracted and modeled can require some upfront effort, the effort is more contained and much lower than trying to generate information from language in the prior channels. This low effort to analyze is in part what has made systems data so popular with People Analytics teams.

Information Density

Density refers to the richness of information each channel provides. Each channel has a certain density of core information, but some channels layer on personal and business nuance, context, and depth.

This factor is where conversation shines and where I believe we've underestimated the information channel. Conversations between people are incredibly dense with information passage for core content, but then also including additional streams of information on the pitch of voice, body language, and facial expressions.

Open-ended surveys try to address the content nuance but still lag conversation on those other human nuances. The systems channel falls far behind then on this factor as systems data is limited to capturing only predefined data points and largely passive data points.

Combining the Tradeoffs

One way to mitigate the strengths and weaknesses of these channels is to pull them into a narrative together. For example, systems data can provide a high-level overview of the situation and help frame the story, survey data be used to capture precise additional information needed for a study, and then follow-up, conversations can provide a much deeper understanding of the context of the problems at hand.

While combining HRIS output with surveys and conversations can be challenging, translating all three into workforce information is what allows us to pull them both into a coherent narrative. For example, the information generated from the systems channel, “what they do”, may tell a story that there is a high turnover rate among a specific demographic within an organization. Relying solely on systems information, we may jump to the conclusion that this demographic is not a good fit for the company.

However, by also listening to "what people say they do" through engagement surveys, we may discover that this demographic is leaving because of a lack of training or career advancement opportunities. Furthermore, if we listen to "what people say" in follow-up conversations between HRBPs and employees, we may identify that there is a particular manager that is not allowing teams to attend trainings. All three channels together create a comprehensive story.

There are instances when each channel should also be used independently. Employee relations professionals' investigations may depend solely on conversations, bypassing surveys or systems. Surveys can offer feedback on large-scale events not covered by systems and where conversations are not feasible. Systems data may be all that is needed for a first-pass analysis or exploratory pass at understanding the organization.

Example

A software development firm leverages information from the systems channel to identify patterns of late-night work activity among its employees. By approaching the data with empathy and understanding, they initiate conversations with affected employees and discover that tight deadlines and unrealistic expectations are causing stress and burnout. As a result, the firm adjusts its project management approach to prioritize employee well-being and work-life balance. They perform a quarterly survey on these topics going forward which finds that the changes they implemented have led to a healthier and more sustainable work environment.

Information Channel Framework for Decision Making

Let’s introduce a more complex diagram now to house this framework. In the following graphic, I’ve laid out the supply chain from each information channel and how it is converted to information. That information can then be combined in a common form and once it is synthesized and analyzed it becomes stories which inform decisions.

Also included in the graphic are the talent strategy for a business (how they want to create strategic advantages with talent) and the experience of the decision maker, which also inform stories. Those two areas have unique influence and in turn are influenced by decisions made by a decision maker. As a final note, this article was focused on internal channels of information, but some additional external channels of information could be external labor market data (information about the context that a workforce sits within) or evidence-based practices (academically validated information).

This flow from information generation to how we inform decisions with stories should be top of mind for any team working in employee listening, people analytics, or HR. We ground ourselves when we are reminded that our goal is to support the HR decision-making process to drive business results.

Now that we have created a framework and explored the value of combining conversations, surveys, and systems data for a comprehensive understanding of the workforce, let's focus specifically on what it means to bring the systems channel into the conversation on listening.

Historically, conversations and surveys have been treated as listening tools, but if the systems channel also generates information about the workforce, we can make the case that we need to listen to employee information through all three channels.

Systems data as Listening

Here are five ways benefits that an HR team can achieve by blending systems data into the conversation on listening along with a fictional story detailing how this could work in practice:

- Engaging HRBPs: By embracing systems data as a form of listening, we can make analytics more accessible to HR professionals who may be more comfortable with traditional listening methods. HRBPs are good at listening and this is another way to do what they are good at. By viewing systems as another way to listen, we can reduce initial fears and skepticism that someone feels when they hear “HR Analytics” or “People Analytics” which will help bring HR into the fold, tapping into their strengths.

Example - Engaging HRBPs: An HR business partner at a retail organization believes that a new schedule that has been set for employees could be causing work-life balance issues. They have had conversations with a few employees which prompted the investigation and after sending out a work-life balance survey they confirmed the issue. However, leadership was still not convinced, so the HR business partner listened to the data from the time-management system to analyze patterns of absenteeism and tardiness among employees before and after the shifts were changed and they found significant increases in each, which they brought into their story. The HRBP took this story which was informed by conversations, survey, and systems data to the leadership team and it convinced them to make a change to the shift schedule, resulting in improved attendance and employee satisfaction.

- Integrated storytelling: This framework creates a more integrated approach to analytics, where we can combine the insights gained from systems data with other channels of information to create a more complete picture of the situation at hand. This integrated approach to methods will lead to better workforce decisions as more information can be brought to bear.

Example - integrated storytelling: A healthcare organization seeks to improve diversity and inclusion within its workforce. By combining data from employee demographic systems, engagement surveys, and focus group conversations, they created a comprehensive narrative that revealed disparities in career development opportunities for underrepresented groups. As a result, the organization implemented targeted mentorship programs and inclusive leadership training, which fostered a more diverse and inclusive workplace.

- Strengthens employee trust: Organizations can demonstrate that they value their employees by actively listening to them through various channels, including systems data. By framing systems data as a form of listening and bringing empathy to bear on that, teams can communicate to employees why they are performing analysis and reduce mistrust related to the analysis of systems data.

Example: A financial services firm transparently communicates their use of systems data to track employee work patterns in order to optimize team productivity. By sharing this information with employees, explaining how data is protected, and explaining how the data would be used to inform the HR decision-making process, employees felt more involved in the process and trust the company's intentions, which leads to increased engagement and commitment.

Reduce debate: Recognizing that all three information channels — conversations, surveys, and systems—are necessary to tell complete human stories fosters a collaborative environment between different teams and functions. This encourages analytics teams, listening teams, and HR business partners to work together to create a comprehensive narrative, rather than focusing on just one aspect of data collection.

Example: In a manufacturing company, there is disagreement between HR and operations teams about the most effective way to allocate resources for employee training. By incorporating data from all three channels—systems data on employee performance, survey feedback on training preferences, and conversations with both employees and managers—they are able to reach a consensus that ultimately leads to more efficient training and improved workforce capabilities.

Human-centered analytics: Framing systems data as listening to the workforce emphasizes empathy and understanding. We should always remember that behind every data point in HR is a human who has a livelihood, friends, family, and a world outside of work. Approaching systems data as listening to employees reminds analytics teams to respect the human behind the data and ensures that the focus remains on the human aspect, rather than treating employees as data points, which ultimately leads to better workforce decisions.

Call to Action

As a reminder for all three systems, transparency is key. Employees deserve to know what information is being gathered, how it is used, and who can see or share information that they have provided or that has been collected about them. Proper data privacy controls, data governance, and agreements between company and employee must be established. Without empathy and these protections, all information channels will break down.

As HR leaders and People Analytics professionals, we must recognize the value of each channel in capturing the complexity and richness of the workforce's experiences, needs, and perspectives. This framework that takes us from information to decisions also shifts us out of our methodology-based functions (e.g. HRBP holding conversations, Employee Listening doing surveys, and People Analytics working with) and reminds us that our common end goal is informing workforce decisions to drive business results.

Upon reading the paper I've gotten the question from a few reviewers around “does this mean the name People Analytics needs to change”. I can see where they're coming from that analytics inspires the stats and management of systems data, but when we look at the core of the word “analytics” it is the science of analysis. I think we are still safe. If we were to go somewhere else someday? I could see us landing on Workforce Decision Support, naming the function on our outcome rather than method, but I don't think that's worth losing the brand we've built under People Analytics today.

As we move forward in an increasingly data-driven world, it is crucial that we remain grounded in empathy and the human aspect of decision-making. Understanding and supporting the individuals that make up our organizations is core to who we are in HR. By actively seeking input from the workforce through all available data channels and embracing a comprehensive listening approach, we will be better equipped to drive meaningful change, foster employee trust, and ensure the long-term success of our organizations.

Margaret Mead hit a point of truth when she said, “What people say, what people do, and what people say they do are entirely different things.", but we’ll end on another quote from Mead which I’ll pass on to you as you think about the work required to get these three channels speaking together instead of apart at your organization:

“Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed, citizens can change the world. Indeed, it is the only thing that ever has.”― Margaret Mead

Many thanks to Mike Merritt, Kyle Davidson, Keith Kellersohn, Peter Ward, Beverly Tarulli, Ethan Burris, Shahfar Shaari, Allen Kamin, Anna Tavis, Al Adamsen, Lyndon Llanes and many others for wonderful conversations on this topic and your feedback! I am grateful and reminded daily of what an incredible community we have in the people analytics world.

Interested in talking to my team to learn more?

Fill out the form below.